On stoppage time.

January 8, 2025

This is a love letter.

I blew out my knee about a year ago, and although I’ve been in rehab for months with the idea of playing rugby again, I’ve decided it’s time to hang up my boots.

One of the major factors that delayed my transition was the fear of losing access to sports. Sports meant everything to me. I had played the majority of team sports in North America at some point or another by the time I graduated high school. Sports shaped me into who I am.

This was 7 years ago, well before this anti-trans misinformation had spread rapidly like a virus. My own internalized transphobia told me that I would be a cheat or a danger to my teammates and opponents if I played women’s sports. It ran so deep that I even ghosted my ultimate frisbee team — literally a co-ed sport — because I was so anxious and embarrassed.

The first year of a trans woman’s journey is terrifying, embarrassing, self-loathing, and often feels hopeless. The world kicks the shit out of you, and all you want is to be invisible yet seen as the real version of yourself. You lose friends and family and partners. People laugh at you and call you slurs. It’s truly awful.

During that first year, I hit an extreme and dangerous low point in my life. I had no queer community, and zero trans friends or role models. I was petrified to go to the grocery store, the gym, clothes shopping, or to use the bathroom in public. Frankly, I wanted to die.

One particularly dark night, I decided that I would get drunk, dressed up, and go to a lesbian bar for the first time. Shortly after I got to Jolene’s in San Francisco, a handsome person with thick black glasses, an under cut, and a goofy smile walked over to me with two beers in hand. They slid one across the table and said:

“Hi, my name is Violet. Do you want to play rugby?”

I wondered to myself if this was how lesbians flirted, so I suavely blurted out the fact that I was trans (I had recently started passing, but was still gaslighting myself), and that I wasn’t allowed to.

They laughed and said that if I was crazy enough to step on a pitch with them, they didn’t care what I was.

That Tuesday I went to my first practice with the San Francisco Golden Gate Rugby Club. Beyond wanting to throw up from nervousness, I suddenly realized that I had absolutely no idea how to play rugby. There wasn’t much explanation, and after some warm-up, we moved right into a tackling drill. I was horrified and fully expected to injure the girl opposite me. I later learned that she was our starting prop who could easily squat 250lbs. Needless to say, I got dumped on my ass.

Before the next practice on Thursday, I asked our coach if we could talk privately. She is one of the best coaches I have had in my entire life, and like all great coaches, she is an extremely intimidating woman. Under my breath, so no one else on the team could hear, I told her that I was a trans woman, but that I really wanted to play if it was allowed. She smiled and told me that she would keep it a secret for now, but would look into the eligibility requirements.

The next day, she sent me the official USA Rugby guidelines. Back then, trans women were eligible if they had been on hormones for at least a year and could periodically prove that their testosterone was in the range for a typical cis woman. I met both criteria and felt hope that I might be able to keep this important part of myself alive as the rest changed.

Unfortunately, USA Rugby is poised to revisit the guidelines this year, likely with a predetermined outcome.

We had a match on Saturday, and I was understandably sidelined. Towards the end of the second half, I watched our winger get her nose bashed in, and she jogged off for something called a “blood sub” (yikes). Coach said I was going in, and the look on my face must have betrayed my horror because she said “run straight, pass backwards, hit someone”.

I was outside one of our veteran players who barked at me to stay behind her, and as the play started, she kicked an errant ball that flipped awkwardly and ended up in my hands. I saw the sideline and I ran as fast as I possibly could until I scored what I assumed was a touchdown. At least, until I heard my entire team shouting at me to touch the ball down. Once I had stumbled into my first try, the team embraced me before the mandatory shooting of the boot. I fell in love.

That team became my family. They were my first queer community, and they expanded my understanding of what kind of woman I could become. They taught me that I could scrum knee deep in mud during the day, and wear red lipstick at the social in the evening. Rugby helped me reform a toxic relationship with masculinity into a healthy one. Rugby freed me from my understanding of gender completely.

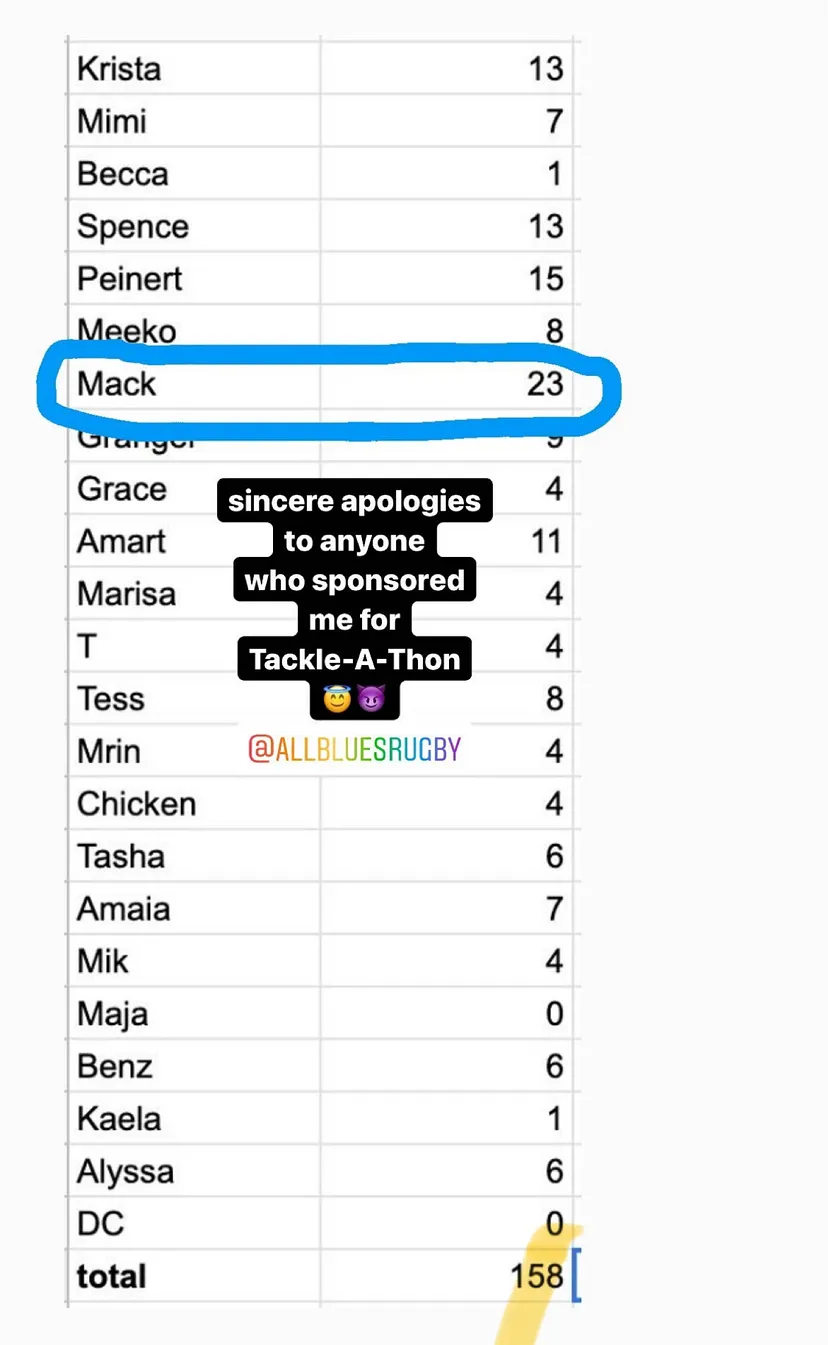

I’ve moved through the positions towards the pack as I’ve aged, strengthened, and learned the game, to find my final home as a flanker. Turns out that protecting others and taking contact is my favorite part of rugby — that’s why I refer to it as my “socially-acceptable form of self-harm”. Plus, I’ve heard from teammates that I’m a somewhat decent tackler.

After a few years at SFGG, including a season as co-Rookie & Recruitment Coordinator with Violet (we would do all of our best recruiting rolling deep as a team at Jolene’s, or through fake Tinder profiles), I moved over to the East Bay to play for the Berkeley All Blues. They were a much more competitive team, and as a club that has always been run by and for women, they were the best organized and most efficient sporting environment I have ever been a part of. I grew more as a rugby player in a single season with the All Blues than in the 3 years prior. Our D2 side went undefeated to a national championship in Atlanta (which we lost), and I stopped off in NYC for a quick, week-long visit on my way back.

This turned into 3 months of sublet hopping, and was my introduction to the New York Rugby Club, where a cis woman snapped my ulna on the first tackle of the first match of the first 7s tournament I played in. So much for my “biologically male” bone density. Regardless, having another high level club be so open and welcoming to me as an out trans woman led to my eventual relocation and a new chapter in my rugby career.

Through all of these years, I was also fighting the wave of transphobic sports bans sweeping the world, which started in 2020 with World Rugby banning a grand total of zero trans women playing at the elite, international level. Although they never listened to a thing we said, a passionate group of trans people and allies engaged over 25,000 people around the world, including USA Eagles like Alev Kelter and Kate Zachary, to help keep Rugby for All (at least in the United States).

When I wasn’t practicing, training, or playing, I was constantly speaking on panels, educating people online, and doing interviews trying to convince the world that I was not a danger to my cis competitors. There was a reason I wasn’t playing for the Olympic squad — I couldn’t even make WPL, which was the highest level of community rugby in the States at the time. I had quietly set that as a goal years ago, just to prove to myself that I could, but my time ran out.

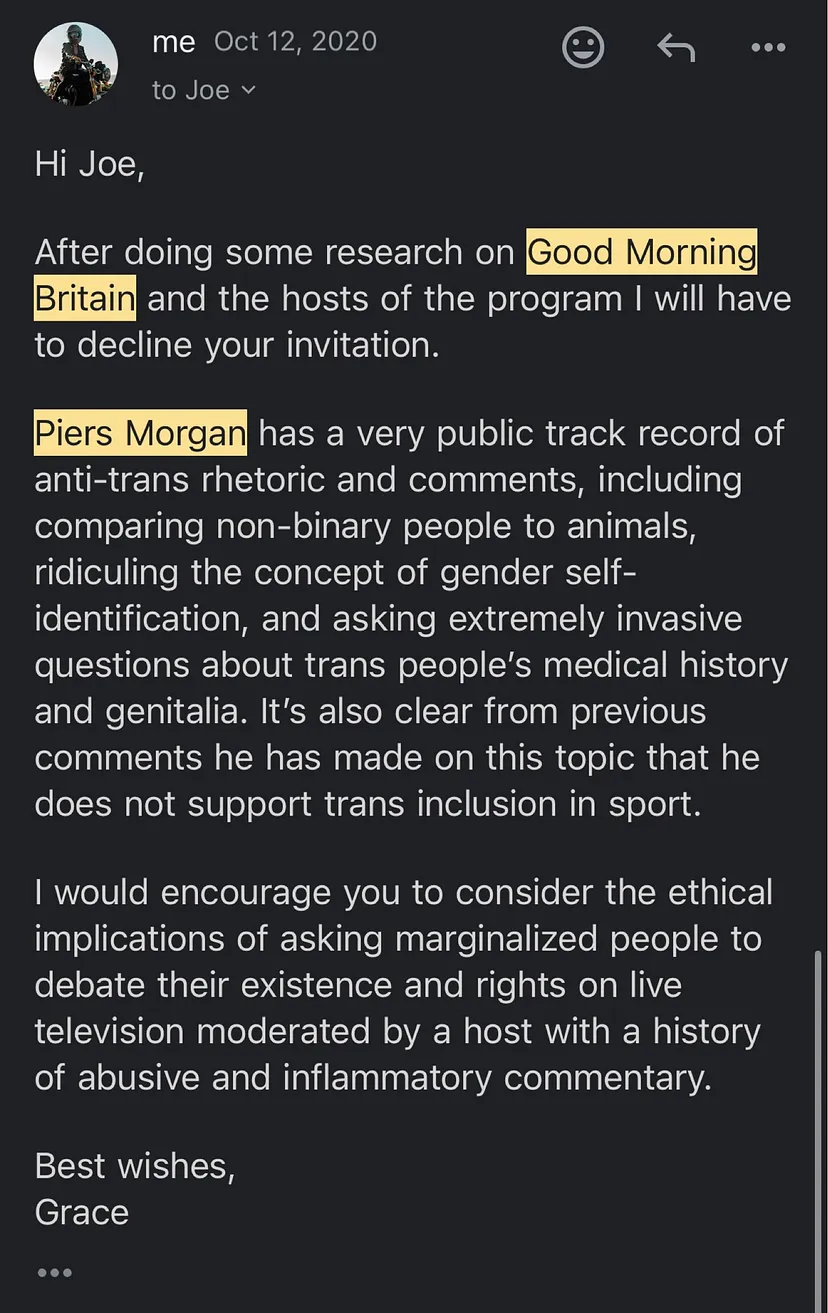

I was interviewed for the New York Times, and Piers Morgan invited me to debate my womanhood on Good Morning Britain (to which I kindly replied “go fuck yourself.”) I met trans players and activists from all over the world, fighting bans and discrimination in their countries as well. I survived Maggotfest twice. I made best friends for a lifetime, and I’ll miss the ex-friends I lost for just as long. I smiled every time I saw my bruises in the shower, knowing that I had earned my place that Saturday. I never once took it for granted.

Rugby made me the woman I am today, and gave me the power to stay alive. Every time I laced up my boots, it felt like a blessing.

The GOP has made it clear that attacking trans people is their number one priority. Even before Trump’s inauguration, members of the Senate just bypassed all typical committee approval processes and tabled a bill that would ban us from women’s sports on a national level. How that would shake out is unclear, but I doubt there is a single person I have lined up alongside or across from who would not speak up — or even lie — if it meant I’d get to play. I love all of you for that.

I am 31 years old and my body is tired. I don’t bounce back like the girls made of rubber who are fresh out of college. I’ve most likely already punched a ticket to life-long arthritis from all of the broken bones and sprained ligaments.

I’d do it all again in a heartbeat.

What matters to me is that I get to go out on my own terms.

They don’t get to tell me how to live and be loved.

They don’t get to force me to hide.

They don’t get to take this from me.

Women’s rugby is one of the greatest gifts I have received in my life, and I will remember every win, loss, tackle, and try. It has been the defining experience of my transition. My very participation in women’s sport is resistance to a system that tries to make all of us small and powerless. I revere every woman and teammate who took me in, mentored me, called me sister, and gave me shelter. You saved my life without knowing it.

It’s really not possible to explain to a cis person the immense feeling of gender euphoria that came from lining up alongside other women on the field, or celebrating in the locker room after a muddy rain-soaked win, or crying together after losing a national championship, or chugging beer with the team that just whooped your ass, or being literally carried off the field when you were injured, or, or, or.

Ironically, there is nothing that made me feel safer than rugby did.

Being a female athlete is similar to my time in men’s sports, but without the toxicity, misogyny, and homophobia. With so much less, women are able to do so much more, creating the kinds of sporting environments that everyone deserves access to. It has healed me, and I guarantee I won’t stay away forever. One day, after I take some time to grieve, I will repay this gift from the safety of the sidelines.

Women’s sports are threatened by chronic underfunding and a lack of media coverage. They are threatened by constant online harassment and bullying. They are threatened by subpar playing conditions and equipment that lead to career-ending injuries. They are threatened by slower rehab due to insufficient conditioning and physical therapy support. They are threatened by sexual violence from their coaches and men’s side players. Olympians and professional athletes shouldn’t have to work second jobs to afford their dreams. On top of all of this, women athletes so often take on the burden of motherhood and caretaking for their children. These women are superheroes and role models.

Ask any true women’s rugger, and I guarantee not a single one will name trans women playing as a threat to the game.

It is getting better, slowly. The world is starting to pay attention. Investors are lining up to get in the door as viewership grows at lightspeed. Leagues are signing game-changing media deals, players associations are renegotiating for more equitable pay, and women’s sports are professionalizing rapidly (looking at you @rugbyevolved). There are high profile stars going on the record to support trans women athletes like @mrapinoe, @sbird10, and @alikrieger. The door might be closing on us right now, but I’m hopeful it won’t stay that way for long.

My final goodbye goes out to every young trans girl who is scared, and who just wants to play sports with her friends. I hope my joy is a promise that there are communities out there full of people that will love and embrace you. No matter what they say, you can be authentically you, and chase your dreams too.

I promise it gets better. Just keep going.

With you, always.